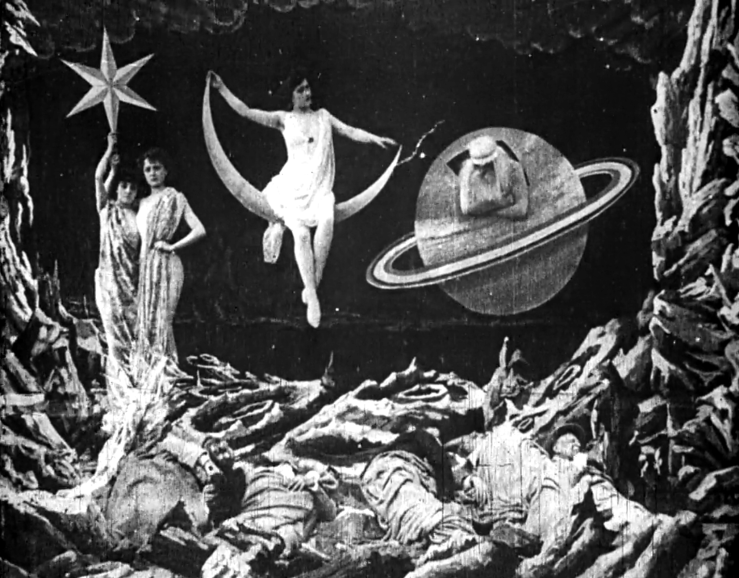

The astronomers land on the moon two separate times. Or at least we see their capsule hit the moon two separate times. The first time, the camera seems to track forward as the celestial body emerges from among silvery clouds, and presently we can see that it has eyes and a mouth, a grandfatherly face whose expression of serenity is shaken when the capsule plows into its right eye, popping it like a zit. The second time the capsule simply plows into a ridge on the surface of the moon, which has gravity and embracing mountain ranges like Coconino County. How do we account for this discrepancy? It seems weird, even for Méliès’s very weird visual language, to show the same event twice in such different ways.

Go back and read the first chapter of Genesis, in which God creates the animals on the fifth day and on the sixth day creates men and women together, and then read the second chapter, in which God creates man on the sixth day, creates animals some time later, then creates woman out of man’s rib. Unless you’re a young-Earth creationist, you will probably accept that these two versions of the creation story represent different traditions, joined without heavy revision by the Biblical editors. Méliès has done basically the same thing here.

In the first image of the moon, those silvery clouds in which the celestial sphere hangs are the last vestiges of the luminiferous ether. Ancient astronomers, unequipped to think about vacuums and gravity, decided that the space outside earth’s atmosphere must be filled with a different form of air in which the planets could float without falling. To describe it, they chose the handy name aether, which meant “shining” air and also referred to a patron spirit in Hesiod’s Theogony, the Greek version of Genesis. It was understood to glow subtly, which explains its silvery sheen in Méliès’s movie. (This idea was more enduring than you’d expect; today NASA scientists colorize images from the Hubble Space Telescope and trick us into thinking that space is full of coruscating golden nebulae.)

Ether lingered in Western science for thousands of years, gradually changing its role as models of the universe morphed, until scientists decided it must be a medium for transferring light. Light was like sound; it couldn’t travel through a vacuum. Physicists therefore chivalrously made room for a hypothetical substance called “luminiferous ether” in their theories. The ether was a completely invisible essence of essences, an absolute frame of reference that underlay the material world, but it was so subtle as to be undetectable until, in 1887, two American scientists set up an experiment to prove its existence.

The Michelson-Morley experiment shot a beam of light through a mirror, splitting it into two distinct beams that would then be reunited on a screen. If the screen showed raggedy concentric circles, then the beams were interfering with one another, which would prove the existence of the ether. What loomed on the detection surface instead was a single circle of sterile light.

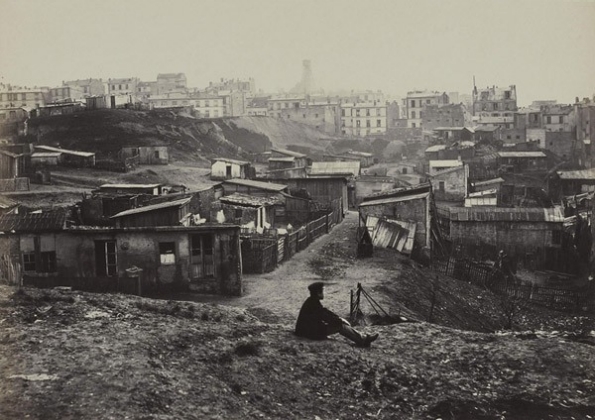

Physics entered a crisis. If there was no underlying medium, then light wasn’t a wave, but if it wasn’t a wave, what was it? Scientists tried frantically to salvage the light wave as a concept, but it’s obvious in hindsight that ether died in 1887. A pair of scientists from Ohio had clawed the last Bronze Age god out of the sky. Méliès made A Trip to the Moon 15 years after the Michelson-Morley experiment, 3 years before Einstein’s “light quanta” introduced the koan-like idea of wave-particle duality. Old certainties are not necessarily overthrown by new ones. Sometime they just wheeze and die, and we have to spend some time in the void before we arrive at new ones. Méliès is hurtling through that void along with his astronomers, looking back on the old world vanishing behind him and anticipating the new one.

In the second depiction of the landing, the astronomers are actually able to leave their capsule and walk around on the surface. The moon here is more than an orb in the sky; it’s a place, a world, with geography that people can interact with as easily as they can climb a hill. Méliès in this case is an oracle. The astronomers watch the Earth rise in the sky: humans in living memory did that. There’s a funny sense of being below the earth, not just below its surface but below the planet itself, which floats above us in strange parody of dawn. The moon is an endless frozen desert, while the sublunar world contains grotesques of terrestrial scenery: limestone water, tree-sized mushrooms, and mute, termite-like people.

The jump to desolation takes place in an eyeblink, in the gutter between two shots. In one we’re in a woolly world of Bronze Age metaphysics, and in the next we’re in an infinite sterile void. Méliès is holding them up side by side: spirit and substance, J and E, wave and particle.

The astronomers have never been in a cave like this before. Some of their colleagues have: decades ago the anthropologist Félix Regnault explored the depths of Lombrives, a system of caves in the Pyrenees famous for sheltering a group of Albigensians from their bloodthirsty pursuers in the 13th century. The Albigensians had wriggled through tight, twisty passages into a vast womblike void in which, by flickering torchlight, they could see glinting spires of limestone and the still green waters of a lake. The ceiling was out of sight in the gloom. Researchers later confirmed that this chamber, which came to be called “The Cathedral”, is the size of Notre-Dame. Regnault would eventually find a deeper, further system of tunnels that led to a chamber four times that size, a cavern so big it seemed bigger than the world outside it. News of this probably reached the astronomers when they were children, and maybe they dreamed of seeing that green lake some day.

The astronomers have never been in a cave like this before. Some of their colleagues have: decades ago the anthropologist Félix Regnault explored the depths of Lombrives, a system of caves in the Pyrenees famous for sheltering a group of Albigensians from their bloodthirsty pursuers in the 13th century. The Albigensians had wriggled through tight, twisty passages into a vast womblike void in which, by flickering torchlight, they could see glinting spires of limestone and the still green waters of a lake. The ceiling was out of sight in the gloom. Researchers later confirmed that this chamber, which came to be called “The Cathedral”, is the size of Notre-Dame. Regnault would eventually find a deeper, further system of tunnels that led to a chamber four times that size, a cavern so big it seemed bigger than the world outside it. News of this probably reached the astronomers when they were children, and maybe they dreamed of seeing that green lake some day.